never miss an issue

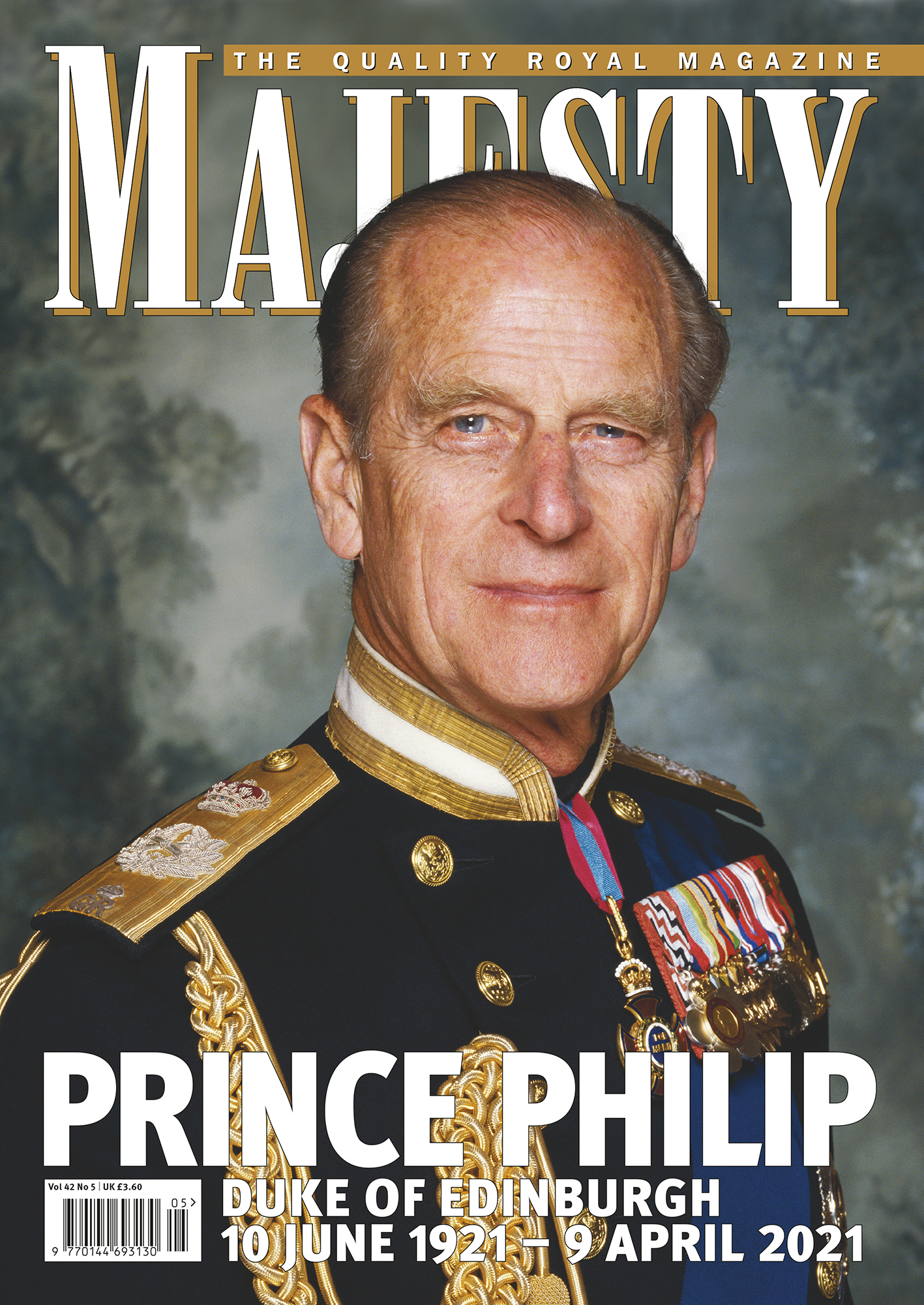

‘It is with deep sorrow that Her Majesty the Queen announces the death of her beloved husband His Royal Highness Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh. His Royal Highness passed away peacefully this morning at Windsor Castle.’

When the announcement arrived from Buckingham Palace at midday on Friday 9 April for that moment the world seemed to stand still. The man who had spent his long life supporting Her Majesty, always two steps behind, was no longer. It was the Prince of Wales and the Duchess of Cornwall’s 16th wedding anniversary and, poignantly for the Queen, the anniversary of Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother’s funeral in 2002.

In accordance with his wishes – the duke wanted as little fuss as possible – and because of the prevailing Covid-19 restrictions, Operation Forth Bridge, the code name for Philip’s funeral plans, was exactly as he would have liked.

The details surrounding his last hours were purposefully vague, but we know that the Duke of York was among the first on the scene, quickly followed by his brother the Earl of Wessex, both of whom live nearby. The Prince of Wales arrived from Highgrove having driven himself from his Gloucestershire estate. The Queen found comfort in taking her two corgi puppies for a walk, something she does when she is stressed or needs time to herself; Philip called it her ‘dog-walking mechanism’.

The duke will be remembered for so many things, but in terms of lasting achievements he typically put his name to very few. He has written volumes of philosophical musings on the meaning of life, largely forgotten or out of print, while books on his so-called gaffes can be found in bookshops categorised as ‘wit and wisdom’.

Prince Philip was full of inventive ideas and besides coming up with a rather mundane-yet-practical boot scraper that didn’t drop muddy debris, he designed jewellery for his wife, including her diamond engagement ring and a bracelet. He also put forward the idea of the stained-glass window depicting the firefighters who saved the castle during the fire of 1992, among others, for the restored private chapel at Windsor where he lay in the days before his funeral. Full coverage will appear in our next issue.

An American friend of mine, whose husband was an international trustee of the Duke of Edinburgh’s Award Fellowship and travelled extensively with Philip and his private secretary, the late Brigadier Sir Miles Hunt-Davis, summed up the duke in a way few, to my mind, have managed to eclipse.

Many people found Philip challenging, she explained, but he was charismatic – a unique character; one of a kind. If you could hold your own, he was a great companion and always made an impact. He set the standard and expected you to meet it.

You never knew what he was going to say, and many comments over the years have been – quite rightly – called out for the offence they have given. Despite the duke’s ability to keep up with the latest in science innovation or environmental issues, he was not always successful in recognising how society was evolving. One could blame his age and say this is down to the generation he belonged to, but it is regretful nevertheless as for many it overshadows the many skills and strengths he has shown during his long tenure as consort to our Queen.

In my experience, his mind was very quick and he enjoyed being around people who could keep up with him. I have often described Philip as a whirling comet with bits shooting off in different directions. I think he would be happy with that.